Passing the German reform of parental leave took almost ten years of work, but when it finally was lauched it had a significant positive effect on mother's employment rate. Yet legacies of a traditional family model in many of the public policies persist

Parental Allowance in Germany,

a success story

A major parental allowance reform was enforced in Germany in 2007. The preparatory work had been carried out by the Red-Green coalition which governed Germany between 1998 and 2005 under Chancellor Gerhard Schröder. Renate Schmidt, the Family Minister at that time, commissioned some experts to evaluate the option of introducing an earnings-related parental allowance along the lines of the Swedish parental insurance. Before she got the possibility to enact the reform, the Grand Coalition of Conservatives and Social Democrats took over government. Ursula von der Leyen, a conservative, replaced Renate Schmidt as Family Minister. Although the Conservatives had pleaded for a child-bonus in the pension insurance ( meaning reduced pension insurance contributions for parents) in their election campaign von der Leyen changed her mind and introduced the new parental allowance scheme that the Social Democrats had worked out.

Since then, mothers or fathers who interrupt their employment for childcare get a parental allowance on new terms. He or she gets 67% of his or her former net income, the minimum and the maximum amount being, respectively, 300€ and 1.800€. One parent is only allowed to use 12 months of the parental allowance. Two additional months (bonus months also called “partner months”) are granted if they are used by the ‘other’ parent, mostly by the father. The “old” parental leave scheme granting up to three years remains in place. So, fathers or mothers can still stay at home for up to three years and have legal protection against dismissal but they receive a wage replacement for one year only. The aim of the reform was to increase the birth rate, to foster mother’s fast re-entry to the labour market, to increase father’s childcare participation, and to secure family income within the first year of the child.

Two major objections were raised in the Parliamentary and public debates. Conservative politicians accused the paternal leave - the partner months – to interfere with the educational freedom of parents and to spread propaganda in favour of a one-sided family model, the two-earners family. The second objection was the middle class bias of the reform. Left-wing politicians emphasized the fact that housewives, students or low-wage earners would only receive 300€ a month for one year instead of the two years they were entitled to under the former regulations which granted this benefit as means-tested parental allowance.

The next conservative Family Minister from the Liberal-Conservative government which came into power in 2009, Christina Schröder, planned to extend the partner months to four months, but the financial crisis left its mark. Due to financial restrictions, she was instead led to lower the wage replacement rate from 67% to 65% for middle incomes (from 1.200€ onwards). Furthermore, starting from 2011 parental allowance will be counted against certain unemployment and social benefits. This strengthened the selective character of the reform.

Germany, who came through the crisis relatively unscathed, recently added yet another new feature to the parental leave scheme. From July 2015, parents can work part-time and receive parental allowance up to two years, the so called “parental allowance plus”. In this case the wage replacement refers to the (part-time) income which is foregone. Furthermore, parents get four more months of paid parental leave if both work part-time (between 25 and 30 hours per week). Two parents working part-time can thus receive a part-time allowance for a maximum of 28 months. This reform was introduced under the new social-democratic family minister, Manuela Schwesig. The alleged aim is to support a more just and fair (care) work sharing between mothers and fathers.

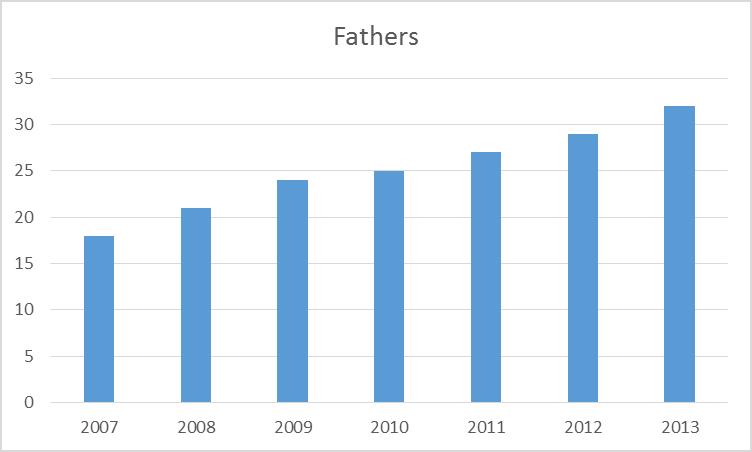

The new parental allowance introduced in 2007 soon became a success story in several respects. First, the 26% figure for all mothers with children under three years that had been employed in 1996 rose to 31.5% in 2011. Most of these mothers, nearly 70%, work part-time (Keller/Haustein 2012). Furthermore, more fathers are using parental leave. In 2013, approximately one third of all fathers took up parental leave. There is a strong connection between mother’s employment and father’s parental leave: the more mothers work the more fathers participate in caring responsibilities. However, 76% of fathers who are using parental leave stay at home for only two months and a mere 6% take parental leave for one year (Statistisches Bundesamt 2012).

Table 1: Father’s use of parental allowance

Source: Statistisches Bundesamt 2012, several press releases of the Federal Statistical Office

The success of the “new” German family policy can only be understood against the background of the expansion of childcare facilities. Since the turn of the millennium, places for children under three years increased significantly. Currently, day-care places are available for one third of all children under three years. Since 2013, there is a legal claim for a place in a childcare facility for children aged one year and older.

At the same time, several regulations concerning childcare and social security still contradict gender equality and support the modernized breadwinner model with a male main earner and a female supplementary earner and main carer. The German income-tax system, for example, supports female labour market inactivity or working as a so called “mini-jobber”, an employment relationship with an income up to 450€ which is exempted from social security contributions and gives no entitlement to pension or other social security benefits. In 2012, moreover, the Conservative-Liberal coalition introduced a childcare supplement after a controversial public debate. Mothers or fathers who do not use a public day-care place and who care for their babies at home receive 150€ per month in the second and third year of the child. Also, non-employed relatives are entitled to the sickness and long-term care insurance as a right derived from the social insurance of the employed person, mainly the husband. Last but not least, widows are granted a survivor pension which depends on the husband’s former income or pension. All such features support traditional gender roles and ought to be reformed to ensure consistency for a policy strategy that aims at fostering gender equality.

German women in numbers

· 72.3% of women of working age (20-64) work in Germany, about 10 percentage points more than in the EU as a whole. Nearly half of them work part-time (46.1%) one of the highest share within the EU.

· The gender pay gap is relatively high, 23.4%

· The gap in pension income is one of the highest in the EU, 45% for pensioners older than 65

· The fertility rate is 1.4 children for every woman of reproductive age

Literature

Keller, Matthias/Haustein, Thomas (2012), Vereinbarkeit von Familie und Beruf. Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus 2011. In: Wirtschaft und Statistik. Ed. by the Statistisches Bundesamt, Wiesbaden, p. 1079-1099.

Statistisches Bundesamt (2012), Pressekonferenz. Elterngeld: Wer, wie lange und wie viel?