Spanish women face many risks as they are trapped in between a misleading media coverage and the lack of gender impact assessment of policies. The article proposes an analysis of the gendered impacts of the great recession on the Spanish labour market

Spanish women

and crisis effect

Spain is the country within the EU with the highest increase in unemployment during this Great Recession. 3.3 million people have become unemployed since mid-2008, more than doubling the amount of unemployed people before the crisis. During these years of recession, articles and news in mass media have often highlighted as an extremely positive result out of it that the gender gap in unemployment rates was closing down, and thus gender equality was being achieved. Although, it is true that aggregate gender gaps in employment indicators -simply measured by the difference between male and female rates in activity, employment or unemployment- have improved in this recession, this progress has been achieved only by faster declines in men’s employment in the first years of the crisis and a levelling down of men’s position in the labour market.

After five years of deep recession, we cannot state that Spanish women have improved at all their status, either in the labour market or in other socioeconomic spheres. In fact, Spain has slipped 18 positions in the Global Gender Gap Index ranking of the World Economic Forum in the last two years. However, these misguided interpretations of gender equality by the mass media have contributed to consider this recession as a male recession and to lessen the interest in analyzing the gender impacts of the crisis, forgetting that economic crises and recessions have always differentiated effects on women and men because women occupy an unequal and unbalanced position in the labour market, the economy, time and work distribution and access to power and decision-making. If we apply a gender analysis to the impacts of the crisis and fiscal consolidation policies in Spain, we are able to distinguish quite distinct phases in this Great Recession with differentiated outcomes for women and men.

In the first instance, it is true that high gender segregation of the Spanish labour market led to a closing of the gender gap in unemployment rates due to a massive destruction of male jobs at an early stage of the crisis, as the sectors mostly hit, such as construction and automotive industry, were male-dominated sectors. However, a second phase of the crisis, which runs from mid-2009 to mid-2011 when the crisis spread to the entire Spanish economy but with a more moderate growth in unemployment due to some expansionary economic policies, was characterized by similar increases in male and female unemployment rates. And, in a third phase which starts in the third quarter of 2011, when we began to notice the effects of austerity policies and labour market reforms and the rise in unemployment accelerated again, female unemployment rates have grown much faster in some quarters. In fact, the gender gap in unemployment has again increased from a minimum of 0.14 in the second quarter of 2012 to 1.17 in the third quarter of 2013, with a male unemployment rate of 25.5 and a female rate of 26.67.

Secondly, female employment tend to recover later from the crisis due to a still higher “social tolerance” to female unemployment, "gender-blind" expansionary policies that tend to focus on male-dominated industries and the more negative effect of austerity policies on female-dominated sectors, such as social services, education or health. In the 2nd quarter of 2013, in which unemployment has fallen for the first time in Spain since the start of the crisis, the number of unemployed has decreased in 161.900 for men and only 63.300 in women. One of the most negative impacts on women's employment has been caused by the huge drop in public employment, of -12 per cent from 2011 exceeding the fall in employment in the private sector, as three out of four public jobs destroyed were occupied by women.

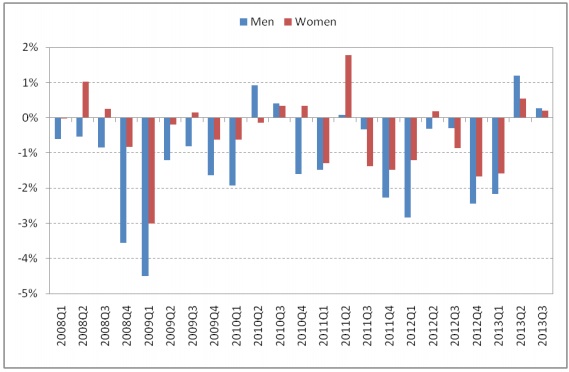

Thirdly, women’s opportunities to find a job are often reduced after a crisis since economic crises usually increase the needs for a family provision of goods and services as they are not any longer provided by the State due to public budget cuts or because they cannot be purchased in the market due to the deterioration of households’ incomes. This intensification of unpaid domestic and care work falls on women because of the still uneven distribution of care responsibilities between men and women, reducing women’s opportunities to go out from unemployment. As we can see in Figure 1, employment population in Spain has started to increase since the second quarter of 2013, but more for men than for women, as it happened in other countries (such as USA or the UK) that had previously left behind the recession. The number of employed people in Spain has increased by 132,100 men in the last two quarters of 2013, while only by 56,400 women.

Figure 1. Quarterly variation in employed population by sex, Spain 2008 Q1-2013 Q3

Source: Own Elaborations on Spanish Labour Force Survey.

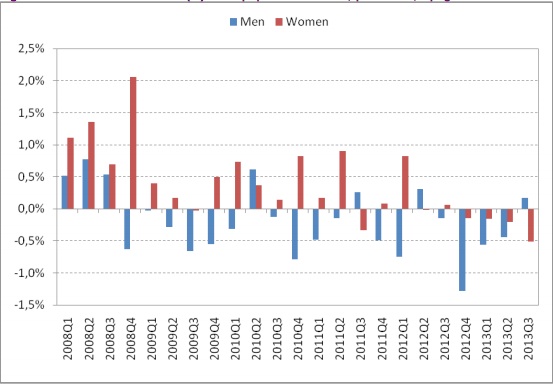

In fact, we may be going back to a labour market that pushes out women, or at least some groups of women, when there are labour shortages. If we analyze by gender the evolution of Spanish labour supply (Figure 2), we find a completely different behaviour for men and women. While male inactivity has been falling since the beginning of the crisis due to a discouraged worker effect caused by the high and increasing unemployment, female labour participation went up till the end of 2012. This added worker effect for women affected mainly over 50 years-old married women whose husbands had become unemployed. However, in 2013 we see a turning point, with more women than men going from activity to inactivity. In the last quarter, 53 thousand women stopped looking for a job while 20 thousand men entered the labour force, mainly Spanish 16-24 years-old men. The majority of women that have moved from activity to inactivity are married Spanish women in their thirties, followed by Latin american women.

Figure 2. Quarterly Variation (%) in active population by sex, Spain 2008 Q1-2013 Q3

Source: Own Elaborations on Spanish Labour Force Survey.

Finally, women tend to go out from a crisis with more precarious and unstable contracts. Although labour reforms and contractionary fiscal policies under this recession are leading us to a radical change in the social model and in the job market, with increased precariousness for both women and men, the over-representation of women in short-term contracts and part-time jobs with low pay and poor conditions place them in a position of great disadvantage. Though part-time contracts for men are increasing very quickly, 72 per cent of part-timers are women. So, in this new model of “flexi-insecurity” for everybody, women may be trapped in the growing categories of underemployed, working poor or at-risk-of-poverty.

These five distinct features by gender do not only show that men and women are suffering the effects of this recession in a very different way, intensity and at different periods of time, they also remind us that progress towards gender equality is not an unstoppable force without potential reversions. If we want to avoid a huge setback in women’s position in the labour market and their life and working conditions, it is essential to take into account that economic crises and policies implemented have unequal effects on women and men. Progress in female labour participation experienced for the last decades in Spain can be seriously paralyzed or take place under unsustainable living conditions, since it is very easy during such a long recessionary period to reformulate rules-of-the-game and gender norms, creating a new sexual division of labour, even more segregated and unequal than before.

----

For a further analysis on these issues, see:

Gálvez-Muñoz, Lina; Rodríguez-Modroño, Paula; Addabbo, Tindara (2013). “The impact of European Union austerity policy on women's work in Southern Europe”. DEMB Working Paper Series 18.

Addabbo, Tindara; Rodríguez-Modroño, Paula; Gálvez-Muñoz, Lina (2013). “Gender and the Great Recession: Changes in labour supply in Spain”. DEMB Working Paper Series 10.