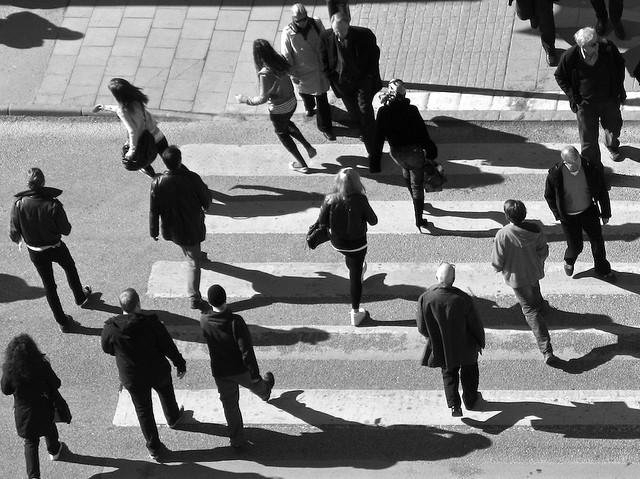

Gender cannot be isolated. Gender interconnects, intermingles, intersects, with other social divisions, such as ethnicity and class. Hence the term, intersectionality

Intersectionality. Putting together

things that are often kept apart

The concept of intersectionality has become widely used in recent years in both academic and policy debates. Intersectional perspectives on interconnections between social divisions, and the complex social phenomena to which they refer, go under many different names, including interrelations of oppressions, multiple social divisions, mutual constitution, hybridities, multiple oppressions, multiplicities. However, the notion of intersectionality, or more precisely intersectional social relations, is not new. This is even if it has sometimes been asserted as such, as when it is rediscovered to address some particular problematic, such as racialized migration or multiple identities.

The term, intersectionality, has been used in many different ways, to refer to, for example, relations between relatively fixed social categories, the making of such categories and their mutual constitution, even the transcending of social categories. Intersectionality can be directed to questions of identity or more generally towards meso and macro structures and processes, organizational, societal or transnational, or to problematizing those distinctions. Approaches to intersectionality range from those prioritising one dominant social division, such as class, with other divisions “added on”; to double or triple power framings, for example, class-gender-race; to more multiple models, including age, disability, sexuality; to multi-factor models. Some uses engage with inter-categorical constructions (focusing on existing relatively fixed categories and relations between them); some focus on intra-categorical approaches (using more provisional categories, as with “people whose identity crosses the boundaries of traditionally constructed groups”); and some favour anti-categorical approaches and deconstruction of categories.[1]

The concept of intersectionality has a rich feminist, anti-racist, indeed intersectional, heritage and history. Intersectionality was, at least implicitly, spoken of in Black feminism and the nineteenth century anti-slavery movement – and probably long before then too. This is clear in the famous speech, “Ain't I A Woman?” delivered in 1851 by Sojourner Truth - Isabella Baumfree (1797-1883) - at the Women's Convention, Akron, Ohio, which can be understood as an impassioned plea for intersectional politics. More recently, the Combahee River Collective - a Black feminist lesbian collective from 1974 to 1980 in Boston, USA - developed the collective statement on interlocking oppressions, racism and identity:

As women, particularly […] privileged white women, began to acquire class power without divesting of their internalized sexism, divisions between women intensified. When women of color critiqued the racism within the society as a whole and called attention to the ways that racism had shaped and informed feminist theory and practice, many white women simply turned their backs on the vision of sisterhood, closing their minds and hearts. And that was equally true when it came to the issue of classism among women.[2]

Probably the most cited scholar on intersectionality is the US Black feminist law professor, Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw. She argued that you cannot understand Black women’s oppression and discrimination by considering only gender or only race: the two are intertwined, including in making legal claims and analyses. Accordingly, she developed the metaphor of crossroads, that is, intersections of roads:

… an analogy to traffic in an intersection, coming and going in all four directions. Discrimination, like traffic through an intersection, may flow in one direction, and it may flow in another. If an accident happens in an intersection, it can be caused by cars traveling from any number of directions and, sometimes, from all of them.

Similarly, if a Black woman is harmed because she is in an intersection, her injury could result from sex discrimination or race discrimination […] But it is not always easy to reconstruct an accident: Sometimes the skid marks and the injuries simply indicate that they occurred simultaneously, frustrating efforts to determine which driver caused the harm.[3]

Many other Black feminists, such as Patricia Hill Collins, Angela Davis, bell hooks and Audre Lorde, have developed this approach further. At the same time, the concept of intersectionality can be understood as a reworking of some persistent themes in modernist social science, such as the place of individuals and groups within complex multi-dimensional societies. The “founding fathers” of sociology – Marx, Weber, Durkheim – prioritized: class, class fractions and factions; multiple power relations; and industrialization and interdependence of divisions of labour under organic solidarity, respectively. Intersectional thinking is clearest in Weber’s writing on intersections of class, status, party.

Debates on intersectionality also derive from Second Wave feminism of the 1960s, especially intersections of gender, ethnicity/race and class: the “big three”. Inspirations have come from critical disability movements and studies, critical studies on men and masculinities, and studies on gender, sexuality and other intersections in workplaces. It is hard to study gender in organizations without examining intersections of organizational position, hierarchy, status, class, occupation, profession and so on. Broader geographical, geopolitical, global, anti-imperialist, transnational, translocal and postcolonial understandings of intersectionality can be employed. Elaborate, multi-dimensional schemes have been developed, for example, by Helma Lutz[4], with multiple ‘lines of difference’, such as gender; sexuality; ‘race’/skin-colour; ethnicity; nation/state; class; culture; ability; age; sedentariness/origin; wealth; North–South; religion; stage of social development. The list is potentially boundless.[5]

Intersectionality figures increasingly in equality (“equality+”) policy development, not least through the work of the UN and the EU, including Anti-Discrimination Directives and initiatives at regional, national and local levels, and in diversity policy and management.[6] Policy may thus become more complex, yet also obscure central dynamics of gender, of ethnicity/race and of class. Indeed an enduring and unfortunate feature of some, perhaps many, intersectional approaches is the downplaying of class.

Of special key interest is in what times, places and situations do intersectionalities, and which intersectionalities, appear most evident for policy attention and development. Intersectional thinking has recently been extended into environmental issues, climate change and transport. In social analysis, policy development or identity, intersectionality can be said to have historically always been there, whether seen or not.

NOTES

[1] McCall, Leslie (2005) ‘The Complexity of Intersectionality’, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 30: 1771-1800.

[2] hooks, bell (2000) Feminism is for Everybody: Passionate Politics. Cambridge, MA: South End.

[3] Crenshaw, Kimberlé (1989) ‘Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex’, University of Chicago Legal Forum, 4: 139-167.

[4] Lutz, H. (2014) Intersectionality’s (Brilliant) Career – How to Understand the Attraction of the Concept? Frankfurt: Institute of Sociology, Goethe University, Frankfurt.

[5] Yuval-Davis, Nira (2006) ‘Intersectionality and Feminist Politics’, European Journal of Women’s Studies, 13(3): 193-209.

[6] Hearn, Jeff and Jonna Louvrier (2015) ‘Theories of Diversity and Intersectionality: What Do They Bring to Diversity Management?’ In Regine Bendl, Inge Bleijenbergh, Elina Henttonen and Albert J. Mills eds. The Oxford Handbook of Diversity in Organizations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.