The banking crisis in Iceland has different effects for men and women

Iceland: male boom,

male crisis

First published: 10/07/2010

In the autumn of 2008 the three main banks of Iceland collapsed. In the years leading up to that time the Icelandic financial sector had grown fast. In 2008, housing prices were falling and the building sector, that had also been booming, almost froze. In the building sector most of the employees are men. Most of the people that were hired in the banks during the boom years were also men. So it should not come as a surprise that the crisis leads to more unemployment among men than women. Before the crisis it was said that it was hard to build a bridge or a house in Iceland, since so many engineers were hired by the banks to design financial instruments. Now engineers, most of them men, have problems getting work, both in banks and the building sector. Women, that tend more to work in the public sector, were more likly to keep their jobs. The fall of the krona has led to increased competitivity of firms in exports and those competing with imports. This has reduced somewhat the increase in unemployment. However, at the same time the depreciation of the krona has led to lower real wages and helped increase the problems people have paying their debts, especially those who borrowed money in foreign currencies. Single parents with children is the family type which has the hardest time paying back their loans since the crisis started. Most of the parents in this group are women. Men that live alone are also having problems paying back their loans, but their problems seem to be less severe than those of single parents, and they have not been as much affected by the crisis.

The upturn in Icelandic economy began in the late 1990's. Economic growth went up from around zero in 1990-1995 to around 5% per annum in 1995-2000. Like elsewhere in the western world, the Icelandic economy cooled somewhat down in 2002 and 2003, but then economic growth went up to 6-8% p.a. till 2007. Unemployment went down from around 5% in the first half of the 1990´s to 2-3% in the years 1998 to 2008. There was shortage of labour, especially unskilled. Real wages grew faster than they had ever done before, for a prolonged period. From 1998 to 2007 real regular wages grew by 50% on average, or 4,6% per year (regular wages are the wage on a monthly basis that employers and employees agree up on, included are payments for shifts and “fixed” (unmeasured) overtime). This was bound to come to an end. The economic boom was in part led by big investments in electrical production and aluminium smelters, topping in 2005 to 2008 with a hydropower plant and an aluminium smelter on the east coast. Financial services also grew fast, especially after two big banks were privatized in 2002 and 2003. International lending markets were easy and domestic lending grew enourmously (together with lending of Icelandic banks in other countries). The financial bubble was mostly felt in the capital area and many people moved to that area, both from other parts of Iceland and other countries. This, together with increased wealth of the native population, led to higher housing prices and increased building of houses in the capital. The building of the the aluminium smelter on Eastern Iceland also led to increased activity in that area, higher housing prices and immigration. However, immigration to Eastern Iceland was in large part of a different character than immigration the capital area, since many foreign workers only stayed for a limited time, many of them in temporary working camps. Most people in the building industry are males, and although women are the majority of staff in banking, the new staff in the banking sector was mainly males (from 2001 to 2008 male employment in banking and insurance increased from 2.100 to 3.800-up by 1.500- while female employment increased from 4.400 to 5.200-up by 800). So one can say that in the men felt the economic bubble more than women. Male employment was rising faster than female employment (male employment rose by 18% from 2003 to 2008, while female employment rose by 11% in the whole country, the difference was larger in the capital area). However, unemployment was similar for men and women in the boom years (that is 6-8% for 16-24 year olds, 1-2% for others). And wages rose much faster for women than men. From 1998 to 2007 real regular wages rose by 42% for men, but by 60% for women. Relative regular wages of women rose from 68% of the wages of males in 1998 to 77% in 2007. Part of the explanation is probably increased education among women. Women are over 60% of university students and they have for some years been the majority of working people with a university degree. However, when one tries to explain the wages of men and women by using explanatory variables, the unexplained part of the wage difference did not changed as much.

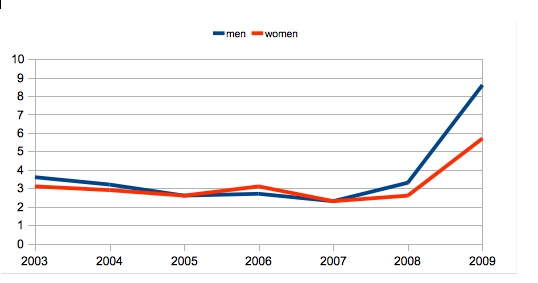

Table 1. Unemployment of men and women in Iceland. Percentage.

Source: Statistical bureau of Iceland

Since the boom was mainly led by males it should not come as a surprice that the crisis has primarily hurt male employment. From 2007 to 2009 male employment has declined by 9% while female employment has declined by only 1%. Unemployment has increased, most among young people, and specially among young men. It is interesting to note that unemployment among young people has increased as much in the rural area as in the capital, even though the bubble primarily existed in the capital. Among 16-24 year old men unemployment went from 8% in 2007 to 20% in 2009. For 16-24 year old women unemployment went up from 6% in 2007 to 12% in 2009. For older people unemployment went up from 1-2% in 2007 to 4-8% for men and 2-5% for women. Fewer are unemployed among those that are 55-74 year old, than those that are younger. Most “striking” when one looks at those numbers is that unemployment is not particularly high in Iceland, when it is taken into account that the financial sector did almost totally collapse. When one studies unemployment statistics one must keep in mind that people facing unemployment tend to dissapeare from the labour market. Many young people decide to go to school when faced with unemployment. The number of 20-24 year old students, that had been declining for some years increased by 4% from 2007 to 2008 and by 9% from 2008 to 2009. The main explanation of relatively low unemployment in Iceland, everything taken into account, must lie in the fact that the Icelandic króna fell very fast in 2007 and 2008, and real wages fell fast. From 2007 to 2009 real regular wages fell by 12% on average. This means that exports and industry and services competing with imports are much more competitive than before. Perhaps it is not surprising, that men´s real regular wages have been falling more than those of women. From 2007 to 2009 real regular wages of men fell by 14%, while real wages of females fell by 9%. It is tempting to explain the increase of female wages relative to men's wages with the fact that the crisis seems to have struck men harder than women. However, the recent increase in relative female wages seems to occur with similar speed as it had done for a decade before the crisis or so. Still, regular wages of women are only 81% of those of men in 2009, up from 68% in 1998. The difference can in part be explained by the more frequent occurance of overtime among men (regular wage are fixed monthly payments, including fixed, or unmeasured overtime). Among students working market participation is higher among women than among men and fewer female students are unemployed than men. This has not changed after the crisis began. Icelandic statistical bureau has for some years looked at the financial situation of all kinds of families. Fewer families were hit by financial problems at the hight of the economic bubble than before, but it is interesting to note that fewer families' loans are in arriers in 2009 than in 2004 (see Table 2). Part of the explanation is that government has initiated some initiatives to ease problems of repayment of loans, mostly by allowing people to delay repayments. When asked about heavy debt burden, however, more families complain now than in 2004. Single males are having more trouble repaying loans or paying housing rent than before, although the problem has not increased by much. When compairing single females and males one must have in mind that many of the men have children, and they pay contributions to them. Also, it is well known, from Iceland and other countries, that single men usually make less money that those that have a spouse. Out of all family groups, single parents with children are having most problems with paying debt and paying rents. The problems of this group have also increased by far the most since the crisis began (although the percentage of families with loans in arrears is similar to that of 2004). Eighteen procent of those have housing loans or rent in arrears in 2009, up from 10% in 2008. In most of those families the one adult is female.

Table 2. Percentage of homes with housing loans or rent in arrears.

Source: Iceland bureau of statistics.

In mid year 2010 there were 318 thousand inhabitants in Iceland, 0,4% fewer than a year before. The year before the number of inhabitants went down a little bit. Before that the number of inhabitants had not gone down over a whole year since the 1880's, when many Icelanders moved to America. In the boom years men were the majority of immigrants. It is not surprising that men are the majority of those who emgrate in time of crisis. Most of those who emigrate are men with foreign citizenship. Much more balance is between male and female emigrants among those that have Icelandic citizenship. In 2009 almost 20% more men than women with Icelandic citizenship emigrated.

One thing that one most keep in mind is that although many Icelandic men and women are facing unemployment and financial difficulties due to the current crisis, the country's problems are not very deep on an international standard. From 2007 to 2009 GDP per capita in Iceland, on a purchasing power parity basis (that is when you can buy as much for the money in every country), went from number 10 on IMF's list over all the countries in the world to number 15. Most of the cost from the bankrupty of the Icelandic banks is being payed by people that live in other countries.