Stories

The reactions to the discovery of Özgecan Aslan’s body, and President Erdogan's statements about gender-sensitive moral issues show how gender today is framed in Turkey. But what kind of gender trends has Turkey really witnessed in the last decade?

7 min read

The violence against women in Turkey has surfaced once more with the discovery of a 20 years old university student, Özgecan Aslan’s murdered and burned body following the attempt of rape by the driver of the minibus she took to return home. The reactions, that can also be traced from media, show how gender today is framed in the country. At the Women and Justice Summit hosted by the Women and Democracy Association (KADEM) in November President Erdogan stated that “You cannot bring women and men into equal positions; that is against nature because their nature is different”. As usual, Erdogan’s gender frames sparked outrage among women activists in civil society as well as in opposition parties. But what kind of gender trends has Turkey really witnessed in the last decade?

After Ataturk’s reforms in the 1920s, which outlawed polygamy and abolished Islamic courts in favour of secular institutions, the second major reform era related to the status of women has been the period since 2001. (1) There have been changes in the Turkish Civil Code (2001), the Turkish Penal Code (2003), and the Constitution (2004) where the phrase “women and men have equal rights and the state is responsible for taking all necessary measures to realize equality between women and men” was added to article 10. Moreover the beginning of the process of pre-accession to EU in 2004 has been a significant turning point for gender policies of Turkey.

Though Turkey still lacks extensive gender data the national Turkish Statistical Institute (TSI) has established a “Gender Team”, providing gender statistics. Organizations like Ka-Der (Association for the Support and Training of Women Candidates) also contribute to monitoring gender trends (see Ka-Der’s website and its latest 2012-2013 Woman Statistics Report). Thus we can have a fair view of recent trends.

In politics, the number of women MPs in the National Assembly has risen from 24 to 79 out of 550, that is from 4,4% to 14.3 % (but their number in the Council of Ministers has remained the same). Woman mayors increased from 18 to 37 and the rate of women city council members increased from 2.3% to 10.7%.

In education, the percentage of illiterate women, which was 19% in the Regular Report on Turkey’s progress towards accession in 2004, has decreased to 7% in the 2013 TSI Women in Statistics Report.

In economy, from 2004 to 2014 there has been a slight upward trend in female employment rate, from 25.5% to 29.7%, but about one third of the women who are considered as employed are unpaid family workers in the agricultural sector. Moreover, whereas overall employment has continued to grow and unemployment fell in 2012 female unemployment rate has remained very high.

Still more negative are statistics on domestic violence: according to the last National Research on Domestic Violence against Women in Turkey (2009) 40% of women in Turkey is exposed to male physical and/or sexual violence by husband or partner in their life time: this percentage rises to 47% in rural areas and 42% in urban areas. Additionally, Bianet’s Annual Male Violence Report (a Turkish newsletter keeping a tally on male violence cases reported by local, national and internet media) states that in 2013 men killed 10 children and 214 women, raped 167, battered 241 and harassed 161. Neither is the picture improved by the fact that, as a response to a parliamentary question asked by a woman Republican Party MP, Ministry of Justice stated that they do not collect specific data on how many women are murdered or raped by husbands or lovers.

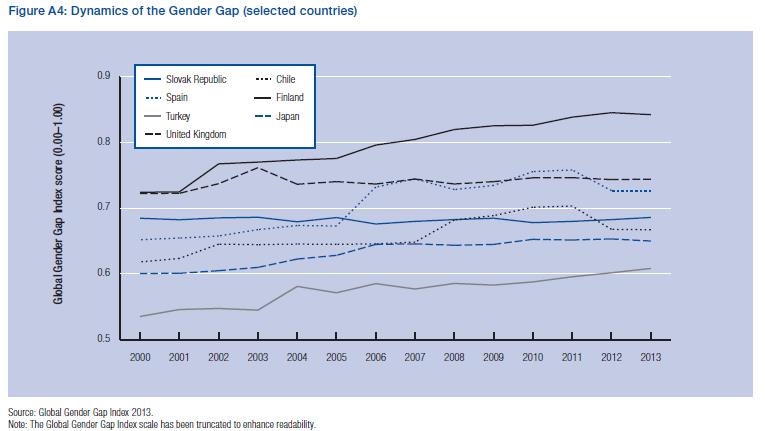

Altogether, international comparisons show that Turkey is still far behind from gender equality. According to the Global Gender Gap Report 2013, the overall rank of Turkey is 120 out of 136 countries; 127th in economic participation, 104th in educational attainment, 59th in health and survival and 103rd in political empowerment. According to the report, apart from the 2003-4 improvements, Turkey’s gender gap in the last 13 years shows no significant decrease (see the graphic below).

This is because, in spite of legal and institutional gender reforms arising from international treaties, the EU candidacy, efforts of feminist organizations (2), (3) over the last decade, the ruling party’s male-dominated, conservative perception sets serious limits to their implementation. AKP primarily considers liberties with reference to Islam and sees woman in first place as member of a family rather than as an individual in society. Thus in 2011 it changed the name of the “Ministry of State for Woman and Family” to “Ministry of State for Family and Social Services” (MSFS) and placed the Directorate General of the Status of Woman (DGSW) under MSFS. Feminists criticized this action as “a step backwards for equality of men and women and for democracy”. They argued that policies targeting women’s conditions, domestic violence and discrimination at work should not be framed as family policies because those are gender-related issues and that what Turkey needs is a Woman and Gender Equality Ministry” [1].

Diverging frames on gender issues between government representatives and women activists also appeared in 2009 when, following the efforts of women activists and MPs, the Committee on Equality of Opportunity for Women and Men (CEOWM) was established under the Grand National Assembly. The name was imposed by AKP during the discussion in Parliament though originally “Gender Equality Committee” had been proposed. Aysun Sayın, of Ka-Der expressed her disappointment: “If people say ‘we are equal in front of the law’ and the committee is called ‘equality of opportunity’, then we cannot demand women quotas or special precautions in employment”[2], whereas Turkey needs affirmative action policies. Nowadays Ka-Der and other woman associations aim to improve the Committee’s impact by demanding that Gender Equality Commissions – which are established in some municipalities – be regulated by the Municipality Law as compulsory commissions.

Again, a battle on gender frames was sparked when on 22/09/2014 the National Education Ministry announced the lift of the headscarf ban in school, allowing girls from fifth grade up to cover their hair in public schools: this enables girls, according to Islamic custom, to start covering their hair when they reach puberty. Conservative groups consider this change as a ‘broadening of liberties’ and AKP government members, such as Education Minister Nabi Avcı, stated that the amendment to the law regulating the attire of high school students was due to “heavy demand”. “When I gathered with students during the start of the academic year, they were waiting for this good news with excitement,” said Deputy Prime Minister Bülent Arınç, recalling his last visit to Bursa, a major city of Turkey. On the other hand the same article still bans body contouring shorts, tights, skirts above the knee, a deep slit skirt, short pants, sleeveless T-shirt and shirts. As a consequence secular and Alevi groups (heterodox Muslim communities remote from the Sunni mainstream) took the opportunity to point once more to the fact that AKP only considers freedom in terms of Islam but stays silent when it comes to lift the compulsory religion lesson (already ruled in ECHR decisions).

Erdogan also takes often public stance on gender-sensitive moral issues. He systematically shares his ideas on demographic policies the implementation of which, in his view, are mainly the responsibility of women, encourages people to have at least three children and, in one of his opening speeches, advised women university students not to be too choosy and not to postpone marriage when they find their match. He maintains abortion is a crime, supported by Minister of Health Recep Akdag who stated that “rape-victim pregnant women should give birth to baby”, which the state would care for if necessary. On the same line AKP MP, Human Rights Commission Chairman Ayhan Sefer Üstün stated: “Rapist is more innocent than the raped victim who had abortion….women in Bosnia had been raped during war, but hadn’t had abortion”[3].

Some unexpected similarities in the two periods of women’s status reform in modern Turkey highlight a historical continuity. In both cases gender policies have been state-led and top-down implemented by two ruling groups which, though embodying opposite ideologies, one secular-progressive, the other religious-conservative, have both used their power to define gender relationships according to gender frames based on men’s perception. In Early Republican Era women’s emancipation and their visibility in public life – enhanced by their beauty, and attire as well as behaviour – was to serve the external image of the Turkish state as a “modern nation”. Today AKP ’s claim to draw the boundaries of appropriate behaviour for a ‘decent’ woman (who should not, among others, laugh loudly in public) provides a set of symbolic representations aiming to keep firmly out of the country notions of gender equality.

NOTES

[1] European Stability Initiative Sex and Power in Turkey, 2007

[2] Ayşe Gunes Ayata & Fatma Tütüncü (2008) Party Politics of the AKP (2002–2007) and the Predicaments of Women at the Intersection of the Westernist, Islamist and Feminist Discourses in Turkey , British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, 35:3, 363-384.

[3] Deniz Kandiyoti, No Laughing Matter: Women and New Populism in Turkey