Recent Turkish elections saw radical changes in parliament composition opening a new political season. Feminists and LGBT activists played a fundamental role in this renewal

What does the Turkish general election

tell for gender equality in politics?

The 7th June general election of Turkey turned out to be the most innovative election in the past 13 years, breaking the path for a new political season in the country. As compared to previous 2011 general elections, AKP lost approximately 10% of its votes, dropping from 49.95% to 40.87%, and from 326 to 258 seats in Parliament: this means loss of the necessary number of seats to pass decisions in parliament and form a government alone.

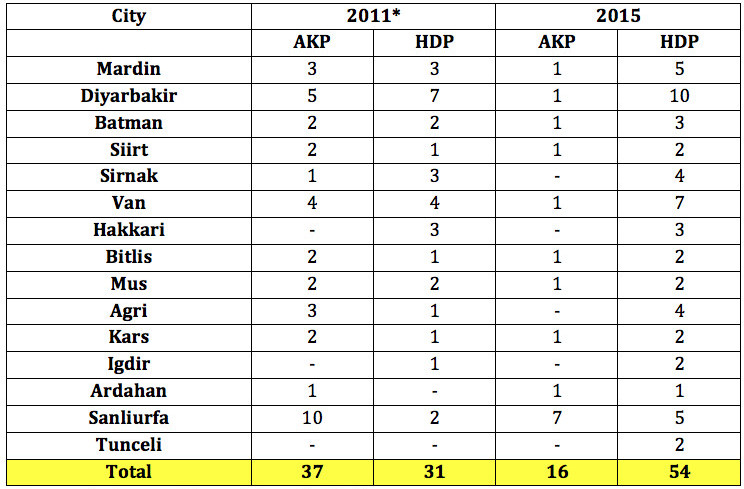

Table 1: 2011 and 2015 General Elections Turnout

* The figures here given for HDP in 2011 Elections refer to MPs elected as independent but also members of the Peace and Democracy Party (BDP), the antecedent of HDP. Source: 2011: the Supreme Electoral Council of Turkey; 2015: Cihan News Agency

On the side of the former opposition the Republican Party (CHP) maintained more or less its previous level with approximately 25% of the votes and a loss of 3 seats. As for the two parties which have consistently increased their votes in thiselection, one is the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) with a 3% increase of its votes which gives him 27 more seats than in the previous parliament. The other – the “new entry” – is the People’s Democracy Party (HDP) which has scored 13.12% votes distributed throughout the country and 80 seats in parliament. Whereas in the past the uncommonly high (and scarcely democratic according to many) 10% threshold of the Turkish electoral system had never alowed Kurdish parties to enter the parliament as such this time HDP, the product of a merging between the Peace and Democracy Party-BDP (the former pro-Kurdish party) and small leftist groups succeeded. In order to understand how votes shifted among parties we may look at some major changes in different cities/regions (Table 2).

Table 2: 2015 General elections - Distribution of Seats in the South East Region

* The figures here given for HDP in 2011 Elections refer to MPs elected as independent but also members of the Peace and Democracy Party (BDP), the antecedent of HDP. Source: 2011: the Supreme Electoral Council of Turkey; 2015: Cihan News Agency

AKP had its most significant decrease in the Southeast region of Turkey, populated heavily by Kurdish citizens in Turkey, where AKP and HDP have always been the two main competitors, leaving usually some 3% of the votes per city in the region to the other two parties ,CHP and MHP. But whereas in 2011 AKP and HDP had obtained more or less the same number of votes, in this election the balance shifted considerably in favour of HDP which took 21 seats from AKP and 2 seats from CHP.

The second area witnessing an important shift in voters’ preferences is that of the 4 major metropolitan cities of Turkey which express approximately 16.6 million votes out of 48.2 million, that is to say 35% of the total [1].

Table 3: 2015 Turkish General Elections - Distribution of Votes and Seats in the 4 major Metropolitan Cities

* The figures here given for HDP in 2011 Elections refer to MPs elected as independent but also members of the Peace and Democracy Party (BDP), the antecedent of HDP. Source: 2011: the Supreme Electoral Council of Turkey; 2015: Cihan News Agency

Table 3 shows that AKP lost approximately 10% of its votes in the 4 major metropolitan cities of Turkey where to-day it has 13 seats lesser than in 2011. And on the other hand in these cities HDP has increased its votes by 8% obtaining 15 seats as compared to the 3 seats won in 2011.. As for the two other parties, their results are consistent with those obtained in the rest of ther country: MHP, with a 2-3% increase of its votes obtains 7 more seats than in 2011 while CHP remains more or less at the same level.

Although the new parliament represents somewhat better than in the past the different ideologies existing in Turkey, the impact of the 2015 elections on gender equality has been rather limited, the percentage of women deputies having only risen from 14% to 18%. As Association for Support of Women Candidates (KA.DER) clearly states, referring to plain numbers, “if there are 453 men and 97 women in the parliament, no one can talk about gender equality”.

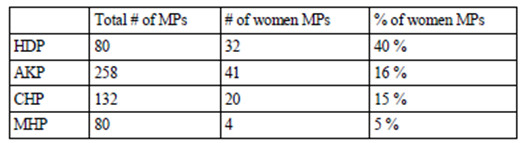

Table 4: Women MPs in the Parliament

Source: Association for Support of Women Candidates (KA-DER)

As can be seen in Table 4, the increase in the presence of women is mainly due to HDP with its 40% of women MPs, 32 out of 82, whereas on the other end conservative MHP allocated only 5% of its seats to women MPs. Moreover, ideologically opposed parties as AKP and CHP allocate almost the same (low) percentage of seats to women: 16% the former, 15% the latter.

Although there is still a long way to go to gender equality in politics, we can still talk about some achievements. To-day women 20 MPs out of 97 are wearing headscarf in parliament -17 from AKP, 3 from HDP. The headscarf ban, in effect since the 1980s, often prevented headscarved women to attend higher education institutions and obtain positions in the professional labor market. It also reached the parliament in 1999 with the case of Merve Kavakci, elected in the Turkish Parliament but prevented from serving her term by the secularists because of her wearing a headscarf [2]. Today headscarved women can participate in political life without any official barrier and in to-day’s Turkish parliament they are present in parties on opposite sides of the political spectrum. Moreover, women MPs in parliament to-day are beginning to represent and struggle against the multiple discriminations in Turkish society. Thus it is not irrelevant that two disabled women have been elected. (one from AKP and one from CHP). And SeherAkcinar Bayar, a 33 years old woman, mother a 4-year-old son, sociologist and activist, elected as MP from HDP, who explicitely defines herself claiming at the same time her Kurdish, her religious and her gender identity, breaks the path for less rigid identifications than in the past.

This is also made evident, appearantly, by the increased number of MPs, mainly from HDP and CHP, announcing their support for LGBT rights in parliament, after Social Policies, Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation Studies Association, SPoD had prepared an agreement for MP candidates declaring that they will defend LGBT rights in the parliament. signed by 30 candidates from HDP and CHP before the election. After elections, LGBT activist MP, CihanErdal could state that “Now there are 80 MPS who will defend LGBT rights in the parliament”. The clear support of feminists and LGBT groups to HDP is deeply related to the negative perception of gender and sexuality policies in the country in the last decade, for instance in regard to Turkey’s top court decision to allow religious marriages outside a legally binding civil marriage. Though unions outside marriage are not formally banned in Turkey, feminists demand compulsory binding civil marriage in order to gain legal protection of minors from forced, underage marriage and protection of women against forced marriages as well as widespread social practices which in a male-dominated society strongly impact on their rights. Feminist activist groups criticized the court’s ruling as opening the path to an increase in polygamy, underage marriages, paid marriages, and infringements of women's rights within marital relations.

Under these circumstances, feminist activists, who are pushing to make gender equality an issue, implemented an active and open support to HDP because of its promises of innovation on these issues. LGBT movements did the same to fight against the increasing homophobia and hate speech cases in the country, making them the topics of political campaigns especially in the last days and signaling the increase of homophobia and authoritarianism as the elections draw close, as when, in a meeting on the 28th of May in Ankara, Erdogan stated that “we won’t appoint a homosexual candidate from Eskisehir”, referring to Turkey’s first openly gay candidate, Baris Sulu, from HDP.

But not only feminist and LGBT activists worked hard for this election. Women from all political parties have been active in demonstrations and backside politics via women’s branch, associations and other networks. In Bursa, one of the mjor metropolitan cities experiencing important changes ion this election, there were several women distributing party flyers to citizens passing in public spaces, saying their preferences aloud in women’s meetings, organizing events like picnics and dinners to gain more supporters or persuade undecided women. The last decade has been one highly contentious in terms of gender and sexuality debates and policies.. On one side there have been increasingly conservative, homophobic and patriarchal discourses - claiming motherhood as a sacred duty for women, defining the heterosexual family as the primary space for women and men, denying homosexual identities – which have also found exprsson in legal and institutional practices. On the other side the same decade has witnessed intense activity by various groups with different political ideologies claiming equal gender and sexual rights and freedom. The last election results clearly reflect this political struggle.

NOTES

[1] http://www.ysk.gov.tr/ysk/content/conn/YSKUCM/path/Contribution%20Folders/HaberDosya/2015MV-GeciciSecimSonuclari.pdf

[2] Cindoglu D. and Zenzirci G. (2008) “The Headscarf in Turkey in the Public and State Spheres”, Middle Eastern Studies, 44 (5), pp. 791-806.